Service workers at TPAC

Last month we had a service worker meeting at the W3C TPAC conference in Fukuoka. For the first time in a few years, we focused on potential new features and behaviours. Here's a summary:

Resurrection finally killed

reg.unregister();If you unregister a service worker registration, it's removed from the list of registrations, but it continues to control existing pages. This means it doesn't break any ongoing fetches etc. Once all those pages go away, the registration is garbage collected.

However, we had a bit in the spec that said if a page called serviceWorker.register() with the same scope, the unregistered service worker registration would be brought back from the dead. I'm not sure why we did this. I think we were worried about pages 'thrashing' registrations. Anyway, it was a silly idea, so we removed it.

// Old behaviour:

const reg1 = await navigator.serviceWorker.getRegistration();

await reg1.unregister();

const reg2 = await navigator.serviceWorker.register('/sw.js', {

scope: reg1.scope,

});

console.log(reg1 === reg2); // true!Well, it might be false if reg1 wasn't controlling any pages. Ugh, yes, confusing. Anyway:

// New behaviour:

const reg1 = await navigator.serviceWorker.getRegistration();

await reg1.unregister();

const reg2 = await navigator.serviceWorker.register('/sw.js', {

scope: reg1.scope,

});

console.log(reg1 === reg2); // Always falseNow, reg2 is guaranteed to be a new registration. Resurrection has been killed.

We agreed on this in 2018, and it's being implemented in Chrome, and already implemented in Firefox and Safari.

self.serviceWorker

Within a service worker, it's kinda hard to get a reference to your own ServiceWorker instance. self.registration gives you access to your registration, but which service worker represents the one you're currently executing? self.registration.active? Maybe. But maybe it's self.registration.waiting, or self.registration.installing, or none of those.

Instead:

console.log(self.serviceWorker);The above will give you a reference to your service worker no matter what state it's in.

This small feature was agreed across browsers, spec'd and is being actively developed in Chrome.

Page lifecycle and service workers

I'm a big fan of the page lifecycle API as it standardises various behaviours browsers have already done for years, especially on mobile. For example, tearing pages down to conserve memory & battery.

Also, the session history can contain DOM Documents, more commonly known as the 'back-forward page cache', or 'bfcache'. This has existed in most browsers for years, but it's something pretty recent to Chrome.

This means pages can be:

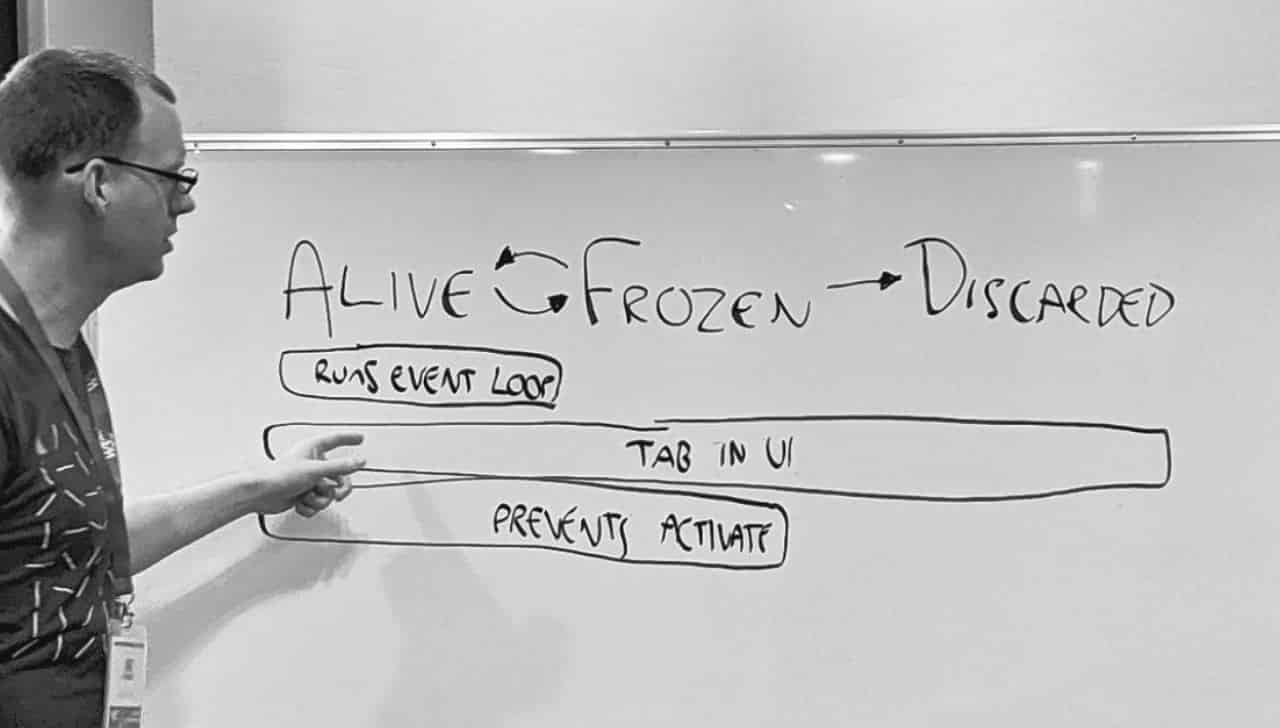

- Frozen - The page can be accessed via a visible tab (either as a top level page, or an iframe within it), which isn't currently selected. The event loop is paused, so the page isn't using CPU. The page is fully in memory, and can be unfrozen without losing any state. If the user focuses this tab, the page will be unfrozen.

- Bfcached - Like frozen, but this page can't be accessed via a tab. It exists as a history item within a browsing context. If a there's session navigation to this item (eg using back/forward), the page will be unfrozen.

- Discarded - The page can be accessed via a visible tab, which isn't currently selected. However, the tab is only really a placeholder. The page has been fully unloaded and is no longer using memory. If the user focuses this tab, the page will be reloaded.

We needed to figure out how these states fit with particular service worker behaviours:

- A new service worker will remain waiting until all pages controlled by the current active service worker are gone (which can be skipped using

skipWaiting()). clients.matchAll()will return objects representing pages.

We decided:

- Frozen pages will be returned by

clients.matchAll()by default. Chrome would like to add anisFrozenproperty to client objects, but Apple folks objected. Calls toclient.postMessage()against frozen clients will be buffered, as already happens withBroadcastChannel. - Bfcached & discarded pages will not show up in

clients.matchAll(). In future, we might provide an opt-in way to get discarded clients, so they can be focused (eg in response to a notification click). - Frozen pages will count towards preventing a waiting worker from activating.

- Bfcached & discarded pages will not preventing a waiting worker from activating. If a controller for a bfcached page becomes redundant (because a newer service worker has activated), that bfcached page is dropped. The item remains in session history, but it will have to fully reload if it's navigated to.

I even put all of my art skills to the test:

Now we just have to spec it.

- GitHub issue about frozen documents & service workers.

- GitHub issue about bfcache & service workers.

- GitHub issue about discarded tabs.

Attaching state to clients

While we were discussing the page lifecycle stuff, Facebook folks mentioned how they use postMessage to ask clients about their state, eg "is the user currently typing a message?". We also noted that we've talked about adding more state to clients (size, density, standalone mode, fullscreen etc etc), but it's difficult to draw a line.

Instead, we discussed allowing developers to attach clonable data to clients, which would show up on client objects in a service worker.

// From a page (or other client):

await clients.setClientData({ foo: 'bar' });// In a service worker:

const allClients = await clients.matchAll();

console.log(allClients[0].data); // { foo: 'bar' } or undefined.It's early days, but it felt like this would avoiding having to back-and-forth over postMessage.

Immediate worker unregistration

As I mentioned earlier, if you unregister a service worker registration it's removed from the list of registrations, but it continues to control existing pages. This means it doesn't break any ongoing fetches etc. However, there are cases where you want the service worker to be gone immediately, regardless of breaking things.

One customer here is Clear-Site-Data. It currently unregisters service workers as described above, but Clear-Site-Data is a "get rid of everything NOW" switch, so the current behaviour isn't quite right.

Regular unregistration will stay the same, but I'm going to spec a way to immediately unregister a service worker, which may terminate running scripts and abort ongoing fetches. Clear-Site-Data will use this, but we may also expose it as an API:

reg.unregister({ immediate: true });Asa Kusuma from LinkedIn has written tests for Clear-Site-Data. I just need to do the spec work, which unfortunately is easier said than done. Making something abortable involves going through the whole spec and defining how aborting works at each point.

URL pattern matching

Oooo this is a big one. We use URL matching all over the platform, particularly in service workers and Content-Security-Policy. However, the matching is really simple – exact matches or prefix matches. Whereas developers tend to use things like path-to-regexp. Ben Kelly proposed we bring something like-that-but-not-that to the platform.

It would need to be a bit more restrictive than path-to-regexp, as we'd want to be able to handle these in shared processes (eg, the browser's network process). RegExp is really complicated and allows for various denial of service attacks. Browser vendors are happy with developers locking up their own sites on purpose, but we don't want to make it possible to lock up the whole browser.

Here's Ben's proposal. It's pretty ambitious, but it'd be great if we could be more expressive with URLs across the platform. Examples like this are pretty compelling:

// Service worker controls `/foo` and `/foo/*`,

// but does not control `/foobar`.

navigator.serviceWorker.register(scriptURL, {

scope: new URLPattern({

baseUrl: self.location,

path: '/foo/?*',

}),

});Streams as request bodies

For years now, you can stream responses:

const response = await fetch('/whatever');

const reader = response.body.getReader();

while (true) {

const { done, value } = await reader.read();

if (done) break;

console.log(value); // Uint8Array of bytes

}The spec also says you can use a stream as the body to a request, but no browser implemented it. However, Chrome has decided to pick it up again, and Firefox & Safari folks said they would too.

let intervalId;

const stream = new ReadableStream({

start(controller) {

intervalId = setInterval(() => {

controller.enqueue('Hello!');

}, 1000);

},

cancel() {

clearInterval(intervalId);

},

}).pipeThrough(new TextEncoderStream());

fetch('/whatever', {

method: 'POST',

body: stream,

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'text/plain; charset=UTF-8' },

});The above sends "hello" to the server every second, as part of a single HTTP request. It's a silly example, but it demonstrates a new capability – sending data to the server before you have the whole body. Currently you can only do something like this in chunks, or using a websocket.

A practical example would involve uploading something that was inherently streaming to begin with. For example, you could upload a video as it was encoding, or recording.

HTTP is bidirectional. The model isn't request-then-response – you can start receiving the response while you're still sending the request body. However, at TPAC, browser folks noted that exposing this in fetch was really complicated given the current networking stacks, so the initial implementations of request-streams won't yield the response until the request is complete. This isn't too bad – if you want to emulate bidirectional communication, you can use one fetch for the upload, and another for the download.

Execute after response

This has become a pretty common pattern in service workers:

addEventListener('fetch', (event) => {

event.respondWith(

(async function () {

const response = await getResponseSomehow();

event.waitUntil(async function () {

await doSomeBookkeepingOrCaching();

});

return response;

})(),

);

});However, some folks were finding that some of their JavaScript running in waitUntil was delaying return response, and were using setTimeout hacks to work around it.

To avoid this hack, we agreed on event.handled, which is a promise that resolves once the fetch event has provided a response, or deferred to the browser.

addEventListener('fetch', (event) => {

event.respondWith(

(async function () {

const response = await getResponseSomehow();

event.waitUntil(async function () {

// And here's the new bit:

await event.handled;

await doSomeBookkeepingOrCaching();

});

return response;

})(),

);

});The privacy of background sync & background fetch

Firefox has an implementation of background sync, but it's blocked on privacy concerns, which are shared by Apple folks.

Background sync gives you a service worker event when the user is 'online', which may be straight away, but may be sometime in the future, after the user has left the site. As the user has already visited the site as a top level page (as in, the origin is in the URL bar, unlike iframes), Chrome is happy allowing a small, conservative window of execution later on. Facebook have experimented with this to send analytics and ensure the delivery of chat messages, and found it performs better than things like sendBeacon.

Mozilla and Apple folks are worried about cases where the 'later on' is much later on. It could be either side of a flight, where the change in IP is exposing more data than the user would want. Especially as, in Chrome, the user isn't notified about these pending actions.

Mozilla and Apple folks are much happier with the background fetch model, which shows a persistent notification for the duration of the fetches, and allows the user to cancel.

Google Search has used background sync to fetch content when online, but they could have used background fetch to achieve a similar thing.

There wasn't really a conclusion to this discussion, but it feels like Apple may implement background fetch rather than background sync. Mozilla may do the same, or make background sync more user-visible.

Content indexing

Rayan Kanso presented the content indexing proposal, which allows a site to declare content that's available offline, so the browser/OS can present this information elsewhere, such as the new tab page in Chrome.

There were some concerns that sites could use this to spam whatever UI these things appear in. But the browser would be free to ignore/verify any content it was told about.

This proposal is pretty new. It was presented to the group as a heads-up.

Launch event

Raymes Khoury gave us an update on the launch event proposal. This is a way for PWAs to control multiple windows. For example, when a user clicks a link to your site, and doesn't explicitly suggest how the site should open (eg "open in new window"), it'd be nice if developers could decide whether to focus an existing window used by the site, or open a new window. This mirrors how native apps work today.

Again this, was just a heads-up about work that was continuing.

Declarative routing

I presented developer feedback on my declarative routing proposal. Browsers are interested in it, but are more interested in general optimisations first. Fair enough! It's a big API & a lot of work. Seems best to hold off until we know we really need it.

Top-level await in service workers

Top-level await is now a thing in JavaScript! However, it's essential that service workers start up as fast as possible, so any use of top-level await in a service worker would likely be an anti-pattern.

We had 3 options:

Option 1: Allow top level await. Service worker initialisation would be blocked on the main script fully executing, including awaited things. Because it's likely an anti-pattern, we'd advocate against it using it, and perhaps show warnings in devtools.

You can already do something like this in a service worker:

const start = Date.now();

while (Date.now() - start < 5000);…and block initial execution for 5 seconds, so is await any different? Well maybe, because async stuff can have less predictable performance (such as networking), so the problem may not be obvious during development.

Option 2: Ban it. The service worker would throw on top-level await, so it wouldn't install, and there'd be an error in the console.

Option 3: Allow top level await, but the service worker is considered ready once initial execution + microtasks are done. That means the awaits will continue to run, but events may be called before the script has 'completed'. Adding events after execution + microtasks is not allowed, as currently defined.

We decided that option 3 was too complicated, option 1 didn't really solve the problem, so we're going with option 2. So, in a service worker:

// If ./bar or any of its static imports use a top-level await,

// this will be treated as an error

// and stops the service worker from installing.

import foo from './bar';

// This top-level await causes an error

// and stops the service worker from installing.

await foo();

// This is fine.

// Also, dynamically imported modules and their

// static imports may use top-level await,

// since they aren't blocking service worker start-up.

const modulePromise = import('./utils');Fetch opt-in / opt-out

Facebook folks have noticed service workers creating a performance regression on requests that go straight to the network. That makes sense. If a request passes through the service worker, and the result was to just do whatever the browser would have done anyway, the service worker is just overhead.

Facebook folks have been asking for a way to, for particular URLs, say "this doesn't need to go via a service worker".

Kinuko Yasuda presented a proposal, and we talked around it a bit and settled on a design a bit like this:

addEventListener('fetch', event => {

event.setSubresourceRoutes({

includes: paths,

excludes: otherPaths,

});

event.respondWith(…);

});If the response is for a client (a page or a worker), it will only consult the service worker for subresource requests which prefix-match paths in the includes list (which defaults to all paths), and doesn't consult the service worker for requests which prefix-match paths in the excludes list.

I was initially unsure about this proposal, because the routing information lives with the page rather than the service worker, and I generally prefer the service worker to be in charge. However, other fetch behaviour already sits with the page, such as CSP, so I don't think it's a big deal.

The API isn't totally elegant, so hopefully we can figure that out, but Facebook have offered to do the implementation work in Chromium, and we're happy for it to go to origin trial so they can see if it solves the real-world problems. If it looks like a benefit, we can look at tweaking the API.

And that's it!

There were other things we didn't have time to discuss, so we're probably going to have another in-person meeting mid-2020. In the mean time, if you have feedback on the above, let me know in the comments or on GitHub.

Oh, also, the venue was next to a baseball stadium, and there was a pub that had windows into the stadium.

That's the second most amazing thing about the pub. The most amazing thing? I asked for a gin & tonic, and I was faced with a clarifying question I'd never experienced before…

"Pint?"

Well…